Next time you look up at the sky and spot one of the 1,100 satellites in orbit, it might be capturing data for your kids’ science project.

In August 2014, US students submitted proposals for projects which would use two weeks of data collected by Ardusatsatellites. The 15 winning teams, selected by astronauts at the Association of Space Explorers, range from middle- and high-school classes to Boy Scout troops and after-school science clubs. Ardusat then sent the winners Space Kits, which contain a range of sensors, including a magnetometer, accelerometer and infrared light sensor. Students wrote experiment code for these Arduino sensors, which are the same as those on Ardusat’s satellites, to measure the data needed for their experiments.

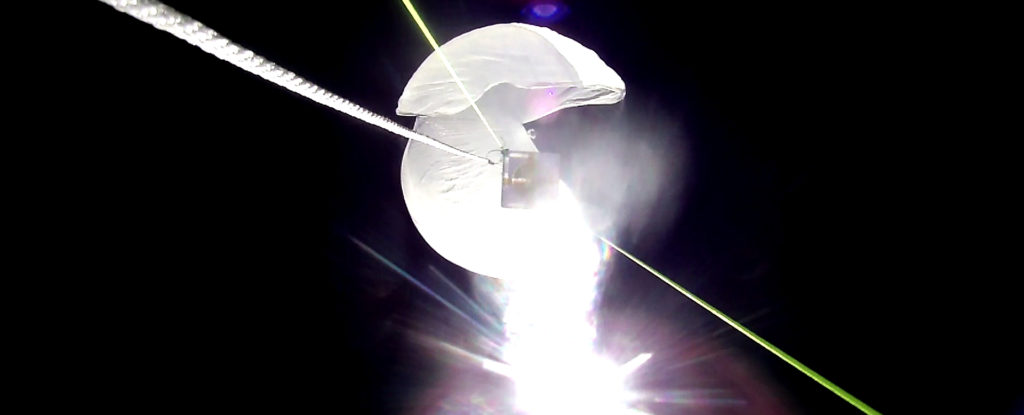

The satellite won’t launch into space until this October. But on April 4, Ardusat launched a high-altitude balloon to let students conduct a trial of their experiments. The students, who designed and coded their experiments in schools from Tennessee to Washington, watched a live broadcast as the balloon and its sensors rose 85,891 feet in the air, landing an hour and a half later.

“We wanted to give them a chance to test it on a high-altitude balloon first, like NASA’s readiness test,” explained Sunny Washington, CEO of Ardusat.

They caught a glimpse of Mother Nature as well. Through a live video stream, students were able to see the balloon traversing 80 miles across Colorado, carrying the code that they had written in the sensors on the balloon. “It was really exciting to watch,” said Lucinda Hemmick, who teaches an Advanced Science Research class at Longwood High School in Long Island, NY. “All the planning and work you put in was in a little box hanging off the balloon, and you could follow its trajectory and see how fast it was moving.”

Two of Hemmick’s students, Jenny (Ruojing) Fang and Jack (Yunjie) Su, designed a project to explore the relationship between climate change and changes in cloud cover. Using data collected from the Ardusat satellite that will be launched this fall, they will compare measurements of radiation reflected back from different Earth surfaces (land, ice regions, the ocean) and evaluate how different surfaces absorbed varying amounts of the sun’s radiation.

“There seemed to be a big gap in understanding how cloud cover impacts the earth and filters radiation from the sun,” explained Hemmick. This year, Fang and Su wrote Arduino code that will measure the satellite’s data with time stamps, and programmed sensors to measure altitude, velocity, and position. They also requested for the satellite’s engineers to attach video sensors so they could visually track cloud cover. When the Ardusat satellite circles the globe during its week of travel in October, Fang and Su will be able to correlate its data with real time information about clouds, as tracked by weather forecasting sites.

Other teams wrote code to collect other data from the satellite sensors. “If you were interested in radiation balance, you’d use UV infrared and luminosity detectors, or a group interested in magnetic differences would use magnetic sensors,” Hemmick explained.

Now it’s time for Fang and Su to start analyzing the 1000MB of Excel data collected by the sensors. The students, who are both juniors, will likely spend their summers analyzing the data and tweaking code for the space satellite. According to Hemmick, these students are happy to spend the summer working on a science project. “They can ask big interesting questions, and start to figure out answers,” she said.

Their enthusiasm for science is what Ardusat’s space launch is all about, explained Washington. “Experiencing something like a high-altitude balloon, where you get to come up with a hypothesis and send your code up 90,000 feet, is an amazing experience to be part of,” she told EdSurge. “There are awesome things happening around us all the time—we have to give students the opportunity to do it hands-on.”

Interested students can apply for the next cycle of the Ardusat space launch competition starting on May 1.