When the taps ran dry in São Paulo neighbourhoods during a drought earlier this year, residents took to storing water in pots and tanks in their homes. The resultant surge in the mosquito population led to the tripling in dengue fever cases across Brazil.

The 500,000 Brazilians who caught the disease – the effects of which range from a fever to death – through mosquito bites in the first three months of the year are but a small fraction of the hundreds of millions infected annually. But some hope for sufferers is at hand courtesy of Oxford-based Oxitec, which plans to fight fire with fire by using genetically-modified mosquitos.

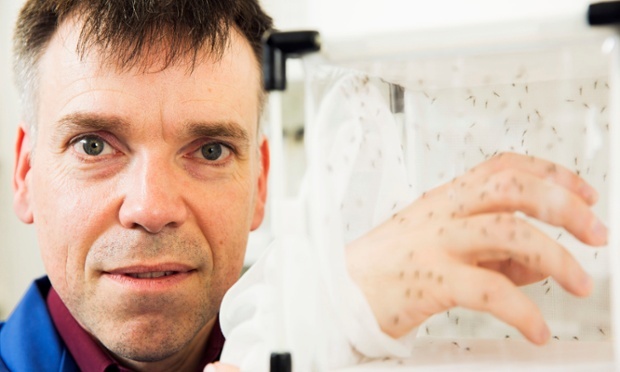

The plan involves genetically engineering the male of the mosquito species which carries the dengue virus but loading a “self-limiting” gene which means their offspring would die before reaching adulthood, thus controlling the population.

When the taps ran dry in São Paulo neighbourhoods during a drought earlier this year, residents took to storing water in pots and tanks in their homes. The resultant surge in the mosquito population led to the tripling in dengue fever cases across Brazil.

The 500,000 Brazilians who caught the disease – the effects of which range from a fever to death – through mosquito bites in the first three months of the year are but a small fraction of the hundreds of millions infected annually. But some hope for sufferers is at hand courtesy of Oxford-based Oxitec, which plans to fight fire with fire by using genetically-modified mosquitos.

The plan involves genetically engineering the male of the mosquito species which carries the dengue virus but loading a “self-limiting” gene which means their offspring would die before reaching adulthood, thus controlling the population.

“It is exquisitely species specific. These males will only mate with females of the same species and not anything else,” says Alphey, who has been shortlisted for a European Inventor Award next month.

“From an environmental point of view, it is extremely attractive. It absolutely minimises off-target effects.”

Initial trials in the Cayman Islands showed a reduction in the female populationof 90%. The engineered mosquitos are typically released into the wild from a tube in the side of a van and driven into the chosen area.

Hadyn Parry, chief executive of Oxitec, says the company will soon start commercialising the dengue product in Brazil before moving on to other countries. Oxitec staff initially will monitor how the mosquitos are released before gradually handing the project over to a body such as a local municipality. The release may take place in phases, says Parry, first to reduce the dengue-carrying mosquito population and then – for example in the case of an island – to stop them returning, by focusing new releases around airports and ports.

After dengue, Oxitec intends to focus on products to tackle agricultural problems such as the diamondback moth, which feeds on crops such as broccoli in the US, and the olive fly, which affects olive plantations across Spain, Greece and Italy. Just like the dengue mosquito plan, “sterile” males would be produced to control the population.

The biggest single challenge facing Oxitec, says Parry, is winning over an often sceptical public. He hopes they can, by stressing that unlike insecticides, where the effects of spraying cannot be differentiated, genetic modification is more targeted so that the gene subsequently disappears from the environment.

“What we see is the vast bulk of people understand what you are doing and are very, very supportive, so in surveys, we get a lot of support. We then get those who don’t understand and need more information and are very conservative and that is absolutely fine. You then get those who are opposed and they tend to be the [anti-] GM crop people and that is the only frustration I find is because what they do is actively put misinformation into the system,” he said.

The method of focusing on the dengue-carrying mosquitos is a highly targeted method and therefore environmentally friendly, says Alphey. It is centred on just one of the approximately 3,500 native species of mosquito, of which there may be between 20 and 40 in any particular area.

One of the concerns raised by the public is that reducing the population of the mosquitos will haffect the overall ecosystem, he says. In the areas where Oxitec is working, such as in south-east Asia or the Americas, the introduced mosquito in question is not part of the local, native ecosystem. When a species has been recently introduced, it is unlikely that any native species is dependent on them for food, says Oxitec.

“Mosquitos in aggregate are not major food for anything. Lots will eat them if they find them but only as a small part of their diet. That is mosquitos in aggregate – this one is a fraction of that,” says Alphey.

The company, which employs 50 people, is expected to expand in size in the near future, says Parry, and will likely move “rapidly” towards an IPO.

What is dengue fever?

The WHO says dengue has spread rapidly in recent years and is widespread throughout the tropics. Although the flu-like illness lasts largely for about a week, around 500,000 people with severe dengue are treated in hospital each year. There is no specific treatment for dengue nor is there a vaccine to protect against it.

•You can read our archive of The innovators columns here or on the Big Innovation Centre website where you will find more information on how Big Innovation Centre supports innovative enterprise in Britain and globally.